I have been blessed with working with a variety of clients over the years- companies included on the Fortune 50, Fortune 500, Fortune 5000, WhoHasAFortune?, and the Inc5000, among other entities. I’ve also worked with and for venture capital and private equity firms, helping them determine if an investment is the proper fit. (That process is typically called ‘due diligence’.)

The difference between venture capital and private equity funds is pretty straightforward. Venture capital is provided to help a company grow, to ultimately be acquired or go public. (These are called the “exit strategies”.) In either exit case, the venture capital entity [or investor(s)] gains its profits from the public offering of stock or via the acquisition of the firm by another entity; it is, in essence, bought out of its interest, returning (hopefully, magnifying) it’s investment capital. That is the goal, of course; sometimes, the venture capital firm is left with not much- if not a loss- from its initial investment(s). But, the ultimate desire of the venture capitalist is to help the nascent entity grow and prosper.

A private equity firm generally has no such lofty goal. It plans to acquire the firm- sometimes in concert with existing management, at other times in opposition to existing management or stockholders. It plans to effect what Joseph Schumpeter termed “creative destruction”. What that term really means is that it plans to pare down the firm, shedding assets (either via sale or abandonment), and, hopefully, restoring it to profitability. That is the ideal. Oftentimes, the private equity firm ends up killing the company that did not need to be killed- but always making a killing for the investors in the private equity firm. (You do recall the movies Wall Street and Money Never Sleeps?)

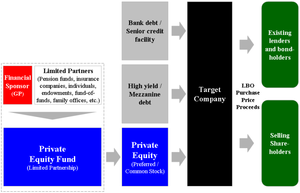

This occurs because the private equity firm searches for what it calls undervalued companies. It buys them with borrowed money, sells the stock back to the public, paying off the debt, meanwhile gobbling up the profits of the firm. It also is paid a fee for its “management” of the firm (a percentage of the gross revenues of the firm), besides those hefty share of any profits it accrues, along the way. (Normally, a company uses those profits to pay dividends to shareholders, pay income taxes, and reinvest in the company to render it stronger, faster, better.) Oh, and private equity gets a special tax break for itself [the shareholders of the private equity firm], claiming these profits to be “carried interest”, a fiction that affords taxation at capital gains rates of about 15% and not the oft-claimed tax rate of 35% that are due to be collected on such profits.

One of the examples of a private equity acquisition that I have already discussed is BankUnited. In this case, the bank was acquired by private equity entities for $ 945 million- and almost immediately sold stock to repay itself $ 500 million of the acquisition costs. So, the $ 11 billion (in assets) bank was acquired for about $ 445 million in cash. Their goal is to sell the bank for at least $ 3 billion, which will net them a 7 fold return. And, if the bank fails, they are NOT on the hook for the losses, either. (You can read the whole saga on my blog here.)

That is my bone of contention with the private equity firms. It’s not that they are harmful to business (although they often are, since they rarely reinvest in the firm acquired and shed employees willy-nilly). No, it’s that they have manipulated the system rules to insure that they make money whether they did their homework properly or not. Whether they helped the company grow back to health or not.

Moreover, the private equity firms, at best, are only interested in short-term profits, rather than the creation of value or augmenting employment. As opposed to venture capital firms, where the emphasis is on longer term growth and value. Which in the larger scheme of things is what makes this country- and its companies- great…

No wonder, Peter Coy, the economics editor of Bloomberg BusinessWeek, has said that “having your company acquired by a private equity firm is like living through a national recession”.

I know I should pay more attention to articles like this — loved how you referred to the “vultures” …. yet, at times it just makes my head hurt!

Well, besides needing to know for business reasons- the two will be in the news for this political season, PeggyLee!

This reminds me of some the schemes with oil in the 1970s where groups were selling the same business back and forth to each other, making and keeping the profit. I’m sure you remember what I am talking about, Roy. The name Sun Oil comes to mind, since they had a plant in South Texas.

Ann Mullen recently posted..Protect Yourself from Medicare Fraud

Unless there’s a Sun Oil that only is in Texas, the Sunoco (Sun O[il] Co[mpany]) has been around a while. In the 70’s, it merged with Sunray DX, took over the Texas Petroleum (which was by then part of Seagrams, which itself had already purchased Texas Petroleum, Dupont, and Conoco- which may be the series of mergers to which you refer), and then Atlantic Richfield (ArCo) and the Gulf headquarters/operations in Philly that needed to be divested by Chevron due to US government concerns about ITS merger), it’s been around a while. But, as I said, you may be referring to Texas Petroleum which was gobbled by Dupont/Conoco/Seagrams shenanigans…

And, Seagrams acquisition did have the flavor of Private Equity, but it was a power play by the next generation of Bronfman’s to change the focus of their holdings.

Roy

Yeah. It was something like that. And each time the things were bought, the price was changed to make money for the players, not the companies. And it was way bigger than just Texas. That was at the same time as the Savings and Loans were playing with stacked decks as well. Then we had the gasoline price hike and suddenly everyone was getting double digit interest rates until the whole thing busted. I never really understood any of it because it was even crazier than I am.

Ann Mullen recently posted..Protect Yourself from Medicare Fraud

I’m late in the day to your post, but I’m here! You really explain this all very nicely, since I don’t know much about the subject I really feel better informed now. Private equity firms sound like Mc Business to me fast food style money with no depth. That kind of thinking is kind of ruining a lot of American business. Not a very good philosophy is it. Not being a good steward of what you are given 🙁 booooo.

Thank you for the article!!

Lisa Brandel recently posted..The Painted Lady by Lisa Brandel

Well, Lisa, it’s not that it’s fast food style- but that the timeframe for a PE firm is short. It wants to buy the firm (with borrowed money), pay that money back, keep the profits for itself (and not for the firm’s growth), make it more efficient (fire workers), and then sell it with capital gains- to boot. In about a short a time as they can get away with. Not that the VC would not want to sell its interest in 3 years, but it’s goal is to grow the company (since it is generally small, when they invest).

On 23 June 2012, Joe Nocera (NYTimes) wrote a piece on Burger King and Private Equity (http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/23/opinion/nocera-burger-king-the-cash-cow.html?_r=1&ref=joenocera ).

A salient quote:

In 2002, Goldman Sachs, along with two private equity firms, TGP and … hmmm … Bain Capital, teamed up to buy Burger King. This is exactly the kind of situation private equity firms like to trumpet: taking over a downtrodden company and nursing it back to health. And to get them their due, Burger King’s new owners did some good, stabilizing both the company and the franchisees, many of whom were in worse shape than Burger King itself.

But the private equity investors also cut themselves an incredibly sweet deal. Their $1.5 billion purchase price included only $210 million of their own money; the rest was borrowed. They immediately began taking out tens of millions of dollars in fees. Four years later, they took Burger King public. But, first, they rewarded themselves with a $448 million dividend. In all, according to The Wall Street Journal, “the firms received $511 million in dividend, fees, expense reimbursements and interest” — while still retaining a 76 percent stake.